Steve Van Dam can remember every boat that has come out of his shop. There’s Jacqueline, a blue and yellow beauty that spends its summers on Lake George in New York. There’s the aptly named Patrician, a 55-foot day-sailing yacht. And there’s the Alpha Z, a sleek powerboat with a hand-carved mahogany dashboard and its name spelled out in stainless steel.

Van Dam Custom Boats has made 58 boats in its nearly 40-year history — just two to four boats each year. At first, this slow, deliberate pace was a simple necessity for a hands-on builder who wanted to be deeply involved in each project and whose modest shop lacked the space for a large staff. But as the business has matured, this focus on meticulous craftsmanship has become a philosophy that makes the boat builder an outlier in an era of mass production and instant gratification.

A Van Dam wooden boat takes eight to 24 months to complete, representing thousands of hours of labor by a team of eight skilled craftsmen. The business likes to have a three-year pipeline of orders. This means that customers who commission Van Dam boats have to wait a few years before they can break their champagne bottle over the bow. But it also means they’re getting a one-of-a-kind object that’s been obsessively constructed, down to the boat’s hand-painted name in gold leaf. The company doesn’t duplicate designs unless the original client gives permission.

It should feel like you’re the center of the universe. Everyone should look at you as you go by.

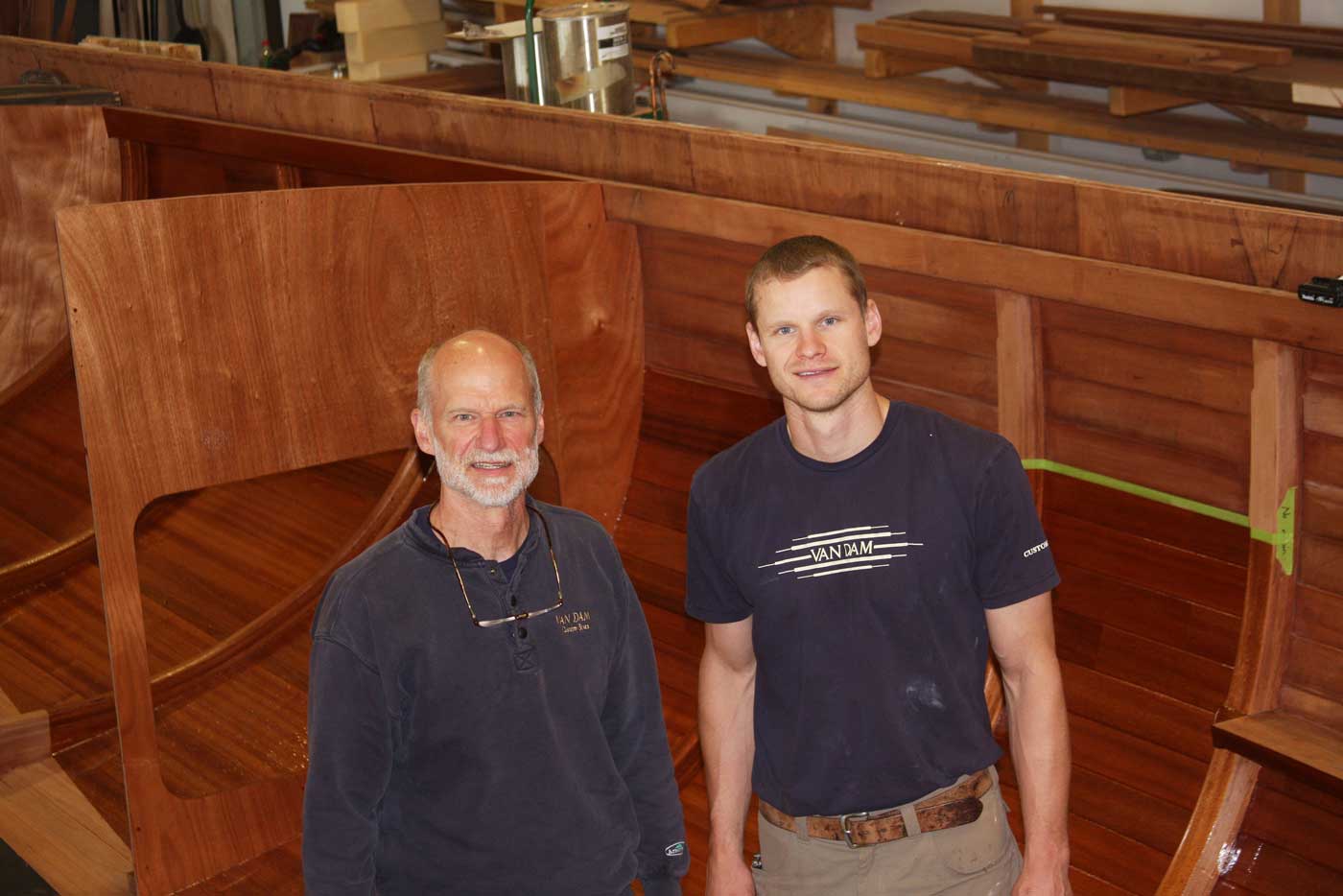

“It’s supposed to feel like that glove they’ve worn forever and it just fits,” says Steve’s son, Ben Van Dam, who is vice president and project manager at the family business. “It’s built for their height and sight lines. It should feel like you’re the center of the universe. Everyone should look at you as you go by.”

The Van Dams love sharing their boatbuilding process, and invite both prospective and current clients to visit their workshop in Boyne City, Michigan, a small town on the southern tip of Lake Charlevoix. The main boatbuilding facility, an airy building that smells of freshly cut wood, hums with a sense of quiet purpose. On a recent visit, one employee was working inside a 34-foot African mahogany powerboat, his head just visible above the hull; in the back, the machine shop foreman was making an exhaust pipe on a manual lathe, tiny curls of stainless steel gathering beneath the cylinder as it took shape.

The Van Dams are private about just two things: their prices and their customers. (Crain’s Detroit Business reported earlier this year that the boats start around $200,000 and can go over $1 million.) Van Dam boats have always been quietly extravagant, but the recession that began in late 2007 pushed even this luxury business to evaluate everything from its prices to its marketing efforts.

In 2009 and 2010, during a brief lull in work, the Van Dams decided to focus on their reputation as “the elite of custom boats, especially custom wooden boats,” Steve says, and to limit production, a move that would boost demand and help them raise prices.

The renewed focus on quality helps address one of Van Dam Custom Boats’ primary challenges: persuading its core clientele to wait for their boats. Some of these customers — affluent individuals 65 and over — worry about how much time they’ll have to enjoy their big investment. The company has started to pursue a slightly younger demographic of people in their 50s and early 60s, but the delayed gratification factor is “definitely a challenge,” Steve says. “We just have to work on making our product so special and so top-shelf that people are willing to wait for it.”

Setting Sail

The issue of wealth, whether his own or that of his customers, was far from Steve Van Dam’s mind when he opened Van Dam Wood Craft in 1977. He started out doing boat restoration and repair projects in a small workshop that he and his wife, Jean, built in her hometown of Harbor Springs, Mich. Steve, who had sailed on a wooden boat on Michigan’s Lake Macatawa as a child and once dreamed of building his own boat to sail around the world, had just completed a multi-year apprenticeship with an Ontario, Canada-based master craftsman named Vic Carpenter.

“When I started the business, really money wasn’t my big issue,” Steve says. “I just wanted to do something I wanted to do, like a lot of old hippies.”

After about a year and a half of restoration and repair work, Steve got his first boat commission from a Milwaukee-based man who had admired the handiwork on the Van Dams’ small wooden sailboat at the Harbor Springs marina. The customer wanted a boat built using a method called cold molding. This technique, which Steve learned during his apprenticeship, involves laminating thin layers of wood with room-temperature epoxies and gently bending the strips around a frame to form the hull. The process creates a light yet strong boat that is far less susceptible to leaking and deteriorating joints than wooden boats held together with metal fasteners.

Cold molding has been around since World War II but didn’t gain wide adoption until the advent of better glues. Vic Carpenter, who died in 2012, was considered a pioneer in adapting epoxies to wooden boat construction. He introduced his work to the brothers who later founded West System Epoxy, the Michigan-based company that supplies glue to Van Dam Custom Boats. Carpenter was also an early experimenter in constructing wooden boats by layering planks of wood, supplanting an older method that involved gluing the planks edge to edge.

The customer who gave Steve Van Dam his first commission “had a lot of faith, because at that point I hadn’t built a boat for anybody,” Steve says. “We just had the business a couple years, and I was kind of the common hippie of the time. I had long hair and a beard.…He was pretty daring to even trust us to do this. But fortunately he did, and we still have a relationship with this person. He just sold the boat; he’s getting elderly now. Nevertheless, that was a huge break for us. And that led to another couple really big breaks — and once you get going, you start to get a reputation, which is huge in this business.”

The Van Dams and their crew pride themselves on perfecting every detail, seen or unseen, from the tidiness of internal wiring to the fact that each grain pattern in the Honduran mahogany used for the boats can be found on both sides — the result of a process called book matching, which splits the logs to create two identical faces. More than half of the 6,000 to 20,000 hours required to build a boat are spent sanding it by hand; after a boat’s final skin is finished, five to seven people sand it for three to five days.

The boats’ interiors, meanwhile, are just as carefully customized to clients’ specifications. For a customer who’d suffered from polio earlier in life and had limited use of his left side, Van Dam put the boat’s controls on his right. Van Dam’s machine shop, which boasts a still-functioning Bridgeport vertical milling machine thought to be from the 1920s or ‘30s, makes everything from custom steering wheels to exhaust pipes out of stainless steel.

They’re still doing things the old way, and it works and it’s amazing and great to see somebody make a business out of that.

Van Dam works with outside manufacturers for certain parts: Gauges come from Classic Instruments, another Boyne City business that makes products like speedometers and fuel gauges for hot rods and classic cars. Seats are made by Special Projects Inc., a Plymouth, Mich.-based company that builds concept cars for automakers. The firm is currently working on some Van Dam boat seats that, at the client’s request, will be fully sculpted out of foam—a high-end process that is rare even in the auto world.

“They’re still doing things the old way, and it works and it’s amazing and great to see somebody make a business out of that,” says Terry Steller, general manager at Special Projects, which was founded in 1983. “[Steve] thinks we’re the gods in the world, and we think it’s the opposite.”

Coming About

The intricacies of boatbuilding came more naturally to Steve than the other aspects of running a business, like finances and accounting. He’d been in business for a decade before he took a regular paycheck. In 1988, the shop got a contract for the Patrician, a large sailboat, and Jean started a master’s degree in health education. She moved downstate for school, bringing the couple’s six-month-old daughter, Brie. Steve and Ben, who was 3 years old at the time, stayed in Harbor Springs and made the two-hour drive every weekend to visit the rest of the family. The new arrangement, with two small children and a spouse in graduate school, was “instrumental in [making] us a little more regimented and really watching to make sure we had enough money to have regular paychecks and things like that,” Steve says. “So it was close to 10 years…before it really felt like we were here to stay.”

Shortly afterward, Jean came on board to handle the company’s finances and bought the shop’s first computer, a Macintosh SE that cost $4,000 — a major investment for the Van Dams at the time. Ben was also a fixture at the family business by then. As a toddler, his father carried him on his back around the shop. By about age 4, Ben had his first job: picking up nails from the floor, at a rate of a penny per nail. Steve and Jean insisted that if Ben and younger sister Brie weren’t otherwise involved in extracurriculars during middle and high school, they had to work at the shop. As a teenager, like every apprentice who goes through Van Dam Custom Boats’ four-year program, Ben’s first woodworking task was to make his own toolbox. He built his first one at the age of 14, and while he doesn’t use his anymore, some of the company’s other craftsmen still carry theirs.

When Ben finished high school, he wanted to start full time at the family business right away, but Steve pushed him to go to college. Ben studied naval architecture at the University of Michigan, getting a compressed and more formal version of the hands-on education his father received over decades. Brie, meanwhile, is pursuing a career as a scientist, leaving Ben as their father’s successor. The two Van Dam men, who share the same crinkly-eyed smile and gregarious manner, are planning the future of the family business together.

“He needs to push a little bit to gain responsibility because I’m not going to just hand it to him,” Steve says of his son. “And he’s learned to do that…These last couple years especially, he’s really stepped up to the plate and said, ‘I’m ready to start swinging.’ And that’s what I was kind of waiting for.”

Six months ago, Van Dam Custom Boats hired Peter Bowers as chief marketing officer to expand the company’s profile in regions like Asia and the Middle East. Bowers talks about things like core demographics with the ease and fluency of someone who’s spent his career in advertising and marketing. Van Dam boats are an “heirloom investment,” he explains, and appeal to individuals who “aspire to have the nicer things in life. They understand that it’s attainable but not something you can just write a check for.”

With Bowers on board, Steve and Ben can refocus their attention on what they like best — building boats.

“Steve and I are craftspeople at heart, business people by necessity—and piss-poor marketers,” Ben says. “Our base tactic is humility. It took a long time to say, ‘We think we do this better than anybody.’”

During Van Dam’s busy periods, like when the shop is getting ready for a big spring delivery, the small crew works five 10-hour days each week, sometimes ramping up to seven 12-hour days. Finding skilled craftsmen has always been a challenge, Steve says, but he’s tried to remedy that by improving pay and nurturing his apprentices. The company’s machine shop foreman, Jesse Brown, arrived at Van Dam as an apprentice in 2003 after attending a boatbuilding school in Maine and evolved into a metalworking specialist.

“The best results are guys who can start at the ground level so they can do every little thing,” Ben says. “They get very well-rounded…. If someone has that drive and some basic hand skills, you can go a long way with that.”

Both Steve and Ben started at the bottom, whether it was Steve working for paltry wages during his apprenticeship with Vic Carpenter or Ben sweeping the floors as a child. Today, with retirement on the horizon — whatever that means for someone who likes to be as hands-on as Steve — the one-time hippie can take stock of his legacy with the wisdom of a seasoned entrepreneur.

“Having a family member step into your business is a pretty special feeling,” Steve says. “Nothing in life really prepares you, or prepared me, for this. It’s a learning experience. But we’re pretty darn fortunate to do what we do and have our customers. And then to have your son come into that, too — we’re pretty lucky people.”