Listen to the audio version of this story. For more, subscribe to our podcast.

At the end of each day, Albert Karoll surveys the floor of his tailor shop, a roughly 500-square-foot room with a picture window that looks out on South Financial Place in downtown Chicago. If the floor is covered in scraps—pieces of plaid and pinstriped wool; strips of fine Italian cotton shirting; loose strands of white basting thread—Karoll knows that the day has been a good one.

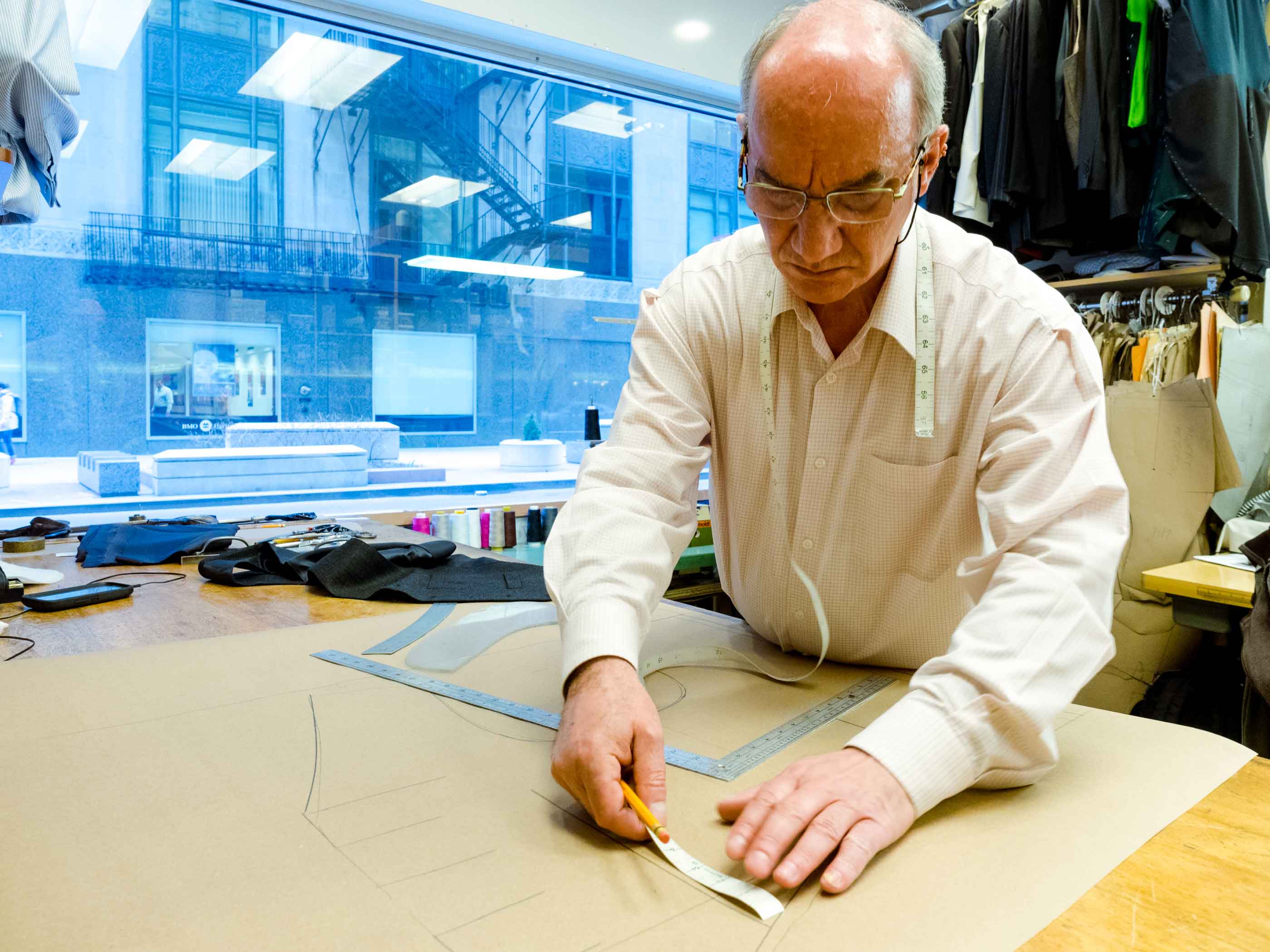

The tailor shop is the heart of Richard Bennett Custom Tailors, which Karoll built in the early 1990s by combining his fledgling menswear business with five Chicago custom-tailor shops whose owners had either died or were retiring without successors. When Karoll acquired those stores, he inherited their clients, patterns, equipment—and perhaps most importantly, their staff. The Richard Bennett workroom is like a living time capsule, its operations on full view to the public through the picture window, and Karoll is as much a preservationist as he is a forward-looking businessman. When passersby peek in the window of his store, they glimpse a century-old process that’s enshrined in the muscle memory of Richard Bennett’s tailors: cutting patterns from brown paper; hand-sewing buttonholes on a jacket; or meticulously pressing a finished garment with a well-worn iron that weighs 25 pounds.

“I have an affinity towards things that are old, as anybody that can walk in our shop can see,” Karoll says. “I value quality. I value heritage and legacy. We built our business on that. …It harkens back to a time when the type of work that we are still doing today had a higher level of value and prestige and respect in the world.”

Chicago was once home to dozens of small custom-tailor shops, founded and run by men who trained in Italy and Eastern Europe before immigrating to cities like Chicago in the early 20th century. Karoll’s business represents what’s left of this old-fashioned industry, where garments are hand-sewn on the premises. His competitors still take measurements by hand but outsource the sewing to tailors in Hong Kong and China, where the cost of labor is cheaper.

At Richard Bennett, a suit travels in circles around the tailor shop to different specialists—with brief sojourns outside its walls only for customer fittings—until completed. A suit takes six to seven weeks to make; in a typical week, the staff finishes three suits. The store’s tailors can also drop everything to make a tuxedo in four days—as they did recently for a top client—or reproduce a garment from a sketch, as they did last year for a customer who wanted a replica of a 19th century English topcoat he saw in a book. A suits typically costs $2,000 to $4,000, while a custom shirt ranges from $150 to $300.

“When I had the chance to design my store, I had always told myself I would put the tailor shop on the window so the world at large could walk by every single day and see what we do, because they are our story,” Karoll says. “We have talent that cannot be found anywhere else in Chicago—master tailors trained in the old-school methodologies: trained to put their hands on clients, make sure the clothing fits perfectly. …People [are] walking by and saying, ‘Oh my God, are people actually making things? What are they doing in there?Are they tailoring stuff, actually?’ Yes, they do. Yes, we are.”

Karoll likes honoring the past while evolving in other ways, whether that means making clothing in updated silhouettes—plain-front trousers, shorter jackets, trimmer fits—or getting into women’s wear. The women’s business is a recent development; Karoll hired two full-time women tailors experienced in making garments for female bodies, instead of simply converting a men’s pattern. Women’s clothing now makes up about 15 percent of Richard Bennett’s business, compared with 5 percent a few years ago. For the most part, Richard Bennett’s female clientele comprises professionals in search of expertly tailored clothing—although in recent years, a small part of that growth has also come from same-sex weddings. The shop makes tuxedos and tuxedo-inspired formalwear for brides.

“A lot of the women who come to us are difficult to fit—that’s one of the reasons a person goes to a custom tailor, whether they’re a man or a woman,” Karoll says. “Some of the women we see are large or very petite, very tall, very thin. They’re not a size six; they can’t go to Bloomingdale’s and buy off the rack. Now, some of our clients are a size six. They just like the quality and the service aspects of what we do. So on the whole, it’s all about fit. It’s always about fit.”

Pieces of a pattern

Karoll keeps 12 to 15 suits in his personal rotation at a time, all made at Richard Bennett. With the arrival of warmer weather, he has switched his somber winter flannels for a cheerier spring wardrobe; during a recent visit, Karoll was wearing a pale blue shirt with a subtle floral pattern and suspenders with bumblebees on them.

But in 1986, when his grandfather took him to dinner at his private club, he was just a broke college graduate with holes in his shoes and three maxed-out credit cards. Karoll was sharing a garden apartment with a roommate on Chicago’s north side, writing freelance pieces for women’s magazines. His grandfather, Herb Karoll, was the founder and owner of Karoll’s Red Hanger Shops, a chain of 14 stores that sold moderately priced menswear. About a dozen family members worked for the company. Industry talk dominated family gatherings, boring Karoll so much as a child that he decided against going into the business.

Herb Karoll, however, had other ideas. Over dinner at Chicago’s Standard Club, Herb “said to me the words that defined the rest of my career,” Karoll recalls. “He said, ‘Writing is a very nice hobby. Now it’s time for you to get a real job.’ And being that my back was up against the wall, I really didn’t have much of a choice, and that’s how I went to work for him in the men’s clothing business.”

Karoll spent his first two years filling in for employees who were sick or on vacation. After a while, he came to enjoy the business and even dreamed of succeeding his grandfather. But the company foundered during the recession of the late 1980s and went out of business in 1991.

The closure was “a very difficult, dark chapter in our entire family,” Karoll says. His grandfather, whom he considered his mentor, never quite recovered from the emotional blow. And Karoll was left searching for his next job.

He decided to stay in menswear but pursue the high end of the market, visiting clients in their homes or offices to take measurements, and working with a contracted tailor to make custom clothing. The plan was to stay lean and avoid overhead expenses like inventory and brick-and-mortar stores. Karoll started with a legal pad of names, a telephone and his Subaru station wagon. He called his business Karoll’s Direct. Of all his cousins and uncles who had worked at Karoll’s Red Hanger Shops, he was the only one who stuck with men’s clothing.

“As I often say, I was the only one dumb enough not to try something different,” Karoll says. “But I always felt good about it because…I learned from the old guys in the back and the guys working in the warehouse and the old-timers that were on the selling floor who would climb over a boulder to not lose a sale. …I took that old-school stuff but recreated it in my own vision to do something that was much more service-oriented, much more personal, much higher quality.”

That old-school mentality remains visible in the way Richard Bennett works today. Karoll, who doesn’t sew, still makes house calls to take measurements. A full set comprises 30 measurements plus digital photos of the client’s front, profile and back. Customers generally return for a couple of fittings as their garments are being made, but good measurements—as well as careful observation of a person’s figure—are crucial for starting the process.

What are the challenges of this person’s posture?” Karoll says. “Look at his shoulder. How does he carry his arms? Is he short-waisted? Is he long-legged? Does he have heavy thighs?

“What are the challenges of this person’s posture?” Karoll says. “Look at his shoulder. How does he carry his arms? Is he short-waisted? Is he long-legged? Does he have heavy thighs? Wait a minute: I see that one hip is higher than the other. You have to look not just at measurements on one plane, but on a 3-D level, because I’m going to hand those measurements off to someone who’s going to create something 3-D. …When I’m measuring someone, I have one shot at it, especially if I’m at his location, so I have to make sure I’m right.”

Richard Bennett’s tailors then create a pattern out of brown paper and use the templates to cut a garment’s component pieces from fabric, making sure any stripes and plaids are matched perfectly in every direction. At the first fitting for a suit jacket or sport coat, the customer tries on what looks like a big vest; there are no sleeves, collar, lapel or linings. After the tailor confirms the posture, shoulder line, chest size and length are correct, the garment returns to the shop for more work. By the second fitting, the jacket will be nearly complete.

Stitching the pieces together

On one morning, James Gordon, a Richard Bennett sales manager who’s worked in menswear for 30 years, opens the store an hour early for Bob Peterson, a 46-year-old executive squeezing in a fitting before work. Peterson, a first-time client, initially came in for a suit, and ended up adding a sport coat and several pairs of trousers to his order. Ioan Sandru, Richard Bennett’s head tailor, moves quietly around Peterson, taking additional measurements and murmuring the occasional question. For his suit, Peterson selected a charcoal gray Tasmanian wool with silver pinstripes from Loro Piana, an Italian maker of luxury textiles.

“I recently lost 40 pounds and decided that I should treat myself to a custom-made suit,” says Peterson, who works in global regulatory affairs for Tate & Lyle, a multinational food-ingredient manufacturer known for Splenda sweetener. “I’ve heard about Bennett for years and always wanted one, and this was a good excuse.”

The Richard Bennett brand has been one of Karoll’s biggest assets since the late ‘90s, when one of his fabric suppliers introduced him to Elmer Miller, then the owner of Richard Bennett Custom Tailors in Chicago. Nick Sander, who had founded the shop about 50 years prior, took the name Richard Bennett from an 18th-century English tailor; Sander thought it sounded more posh. Miller was retiring and looking for a buyer. Karoll’s purchase of Richard Bennett in 1998 was the first in a string of deals that transformed his business from a one-man operation run out of his apartment to an established retailer with full-time employees and a physical storefront.

Karoll combined elements from the businesses he acquired to create a unified story of heritage and a connection to the old-world tailors of Savile Row and Milan. He chose the name Richard Bennett because it was the best-known brand. The store’s canonical founding year, 1929, comes from DeBartolo Custom Tailors, a family-owned business whose clients included former Chicago Mayor Harold Washington.

Karoll also sees his store as carrying on his grandfather’s legacy. “He died shortly after I started my business, so he never saw this,” Karoll says. “I’d say he would be exceedingly proud. He would never admit it, but he would be.”

Today, Richard Bennett employs five full-time tailors with his or her own specialties, whether it’s attaching the sleeves on a jacket or making a vest. The meticulous hand-sewing—even on something as small and overlooked as a buttonhole—is what makes a Richard Bennett suit.

We take pleasure in doing it this old-fashioned way, and we are really the last shop in Chicago of any consequence that’s still doing it this way.

Machines “pull at the same tension for every stitch, whether it’s in the front of the garment, the shoulder, the collar, the sleeve, or the trouser,” Karoll says. “When you have a hand-sewn garment, the tailor knows to create longer stitches, shorter stitches, tighter stitches, or looser stitches at various parts of the garment, which lends itself to a softer fit. …There is inherent value in the process, and that’s one of the reasons we do it. One of the other reasons we do it is because we like to. We take pleasure in doing it this old-fashioned way, and we are really the last shop in Chicago of any consequence that’s still doing it this way.”

Toward the end, the garment is pressed. The tailors use heavy, 50-year-old hand irons that get heated to several hundred degrees. A trouser leg’s crisp fold is created on a machine called a buck press, which sandwiches the garment between two heated surfaces. The top plate applies steam, and the bottom plate uses a vacuum to draw out moisture so the fabric doesn’t become limp. The pressing stage is crucial: Wool fibers expand when they come into contact with heat and steam, then contract and hold their shape as they cool. It’s the tailor’s final opportunity to mold the garment—one last way to impart decades of knowledge of how fabric conforms to the human figure and behaves over time.

“When we take a garment that’s raw and fresh, and press it for the first time, we’re putting memory into the seams, into the creases, into the angles, into the shoulder,” Karoll says. “That’s memory we hope will never go away.”