Some of Nick Horween’s earliest memories of his family’s leather tannery are of taking the train from Barrington, the northern Chicago suburb where he grew up, into the city to visit his father and grandfather at work. The smell of leather would hit him the instant he walked through the front door at Horween Leather Co. When his father returned home, Nick would hug him and breathe in the same scent, which lingered on his father’s jacket.

The smell of leather has followed five generations of Horweens. Nick’s father, Arnold “Skip” Horween III, runs the tannery that Nick’s great-great-grandfather, a Ukrainian immigrant named Isidore Horween, founded in 1905. At that time, Chicago’s railways, water sources and world-famous stockyards provided an ideal location for leather makers and other businesses, like shoe polish and brush manufacturers, that used the meatpacking industry’s byproducts as their raw materials. Today, as the only tannery left in Chicago, Horween’s origins in this old-world economy have become a unique selling point for customers who are championing a revival of consumption based on quality.

Some of Horween’s customers are as old as the tannery itself, with their business relationships stretching back decades. Horween leather has graced the feet of American presidents and the hands of NFL quarterbacks. With global leather production having moved overseas to lower-cost regions like Asia and South America over the last quarter century, Horween has evolved into a maker of high-end leather for luxury goods. It is one of the world’s last remaining producers of shell cordovan, a durable leather derived from horse rumps. Allen Edmonds, a 92-year-old shoemaker based in Wisconsin, uses this leather in its Park Avenue Cordovan Oxfords, which Presidents Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush wore for their inaugurations. The oxfords retail for $650, but cordovan shoes can last for 20 years or more if maintained properly.

“It’s definitely been instilled in me since the very beginning that it’s about the product,” said Nick, who is 30 years old and a vice president at Horween. “If the customer can’t tell the difference and you charge a premium, you’re out of business. So it just has to be the best you can make it. You put all the best stuff into it so you can get the best out of it, and get your price or don’t sell it.”

So it just has to be the best you can make it. You put all the best stuff into it so you can get the best out of it, and get your price or don’t sell it.

Among Horween’s newer customers is Detroit-based luxury goods maker Shinola, which last year began selling its handcrafted-in-the-U.S. products online and in stores like Sak’s Fifth Avenue. The two companies undertook an extensive development process to come up with the right vegetable-tanned leather for Shinola’s watch straps, wallets, journal covers and other items. Chief Executive Steve Bock said he expects his company to do more business with Horween as production ramps up. Shinola is planning to open a small leather goods manufacturing facility within its 60,000-square foot factory space in downtown Detroit.

“The quality immediately comes through,” Bock said of the leather. “There’s a softness and certainly a durability … This is a 100-year-old company that has really built a tremendous amount of expertise over that period of time.”

Slow and steady

Skip still takes the train to work. The station is located across the street from Horween, which has been operating out of its current factory on the North Branch of the Chicago River since 1920. The city designated this industrial corridor as a special manufacturing district more than 20 years ago to protect it from certain kinds of residential and commercial development. The demarcation is stark: While Horween’s longtime neighbors include a tire recycler and a metals refiner, both around 100 years old, a multiplex and a Pottery Barn Kids have sprouted across the river.

As a child, Skip tagged along with his father to work on Saturdays, when the factory used to run for a half day. After the employees went home, his father let him sit on his lap and steer the forklift around the back lot. Skip worked alongside his grandfather, Arnold Horween Sr., for five years and his father, Arnold Horween Jr., for more than 20 before taking over as president in 2002. He remembers Arnold Horween Sr. as a smart and detail-oriented manager who knew every inch of the factory, while Arnold Horween Jr. was a superior mechanic who “could take a pocketful of tools and wade in there.”

Skip’s predecessors taught him that “You don’t make leather at a desk,” he said. “You have to be out in the plant.”

Nick, whose middle name is Arnold, went through the same education. Like Skip, he began working at the tannery during his teenage summers doing “whatever, the worst stuff” — cleaning equipment, tarring the roof. Nick has tried his hand at a number of jobs at the tannery, including feeding cow hides through the “fleshing” machine, a large apparatus that scrapes off fat and deposits it in a bin full of ashy gray sludge.

As he got older, Nick briefly pursued a different route. He studied business at the University of Vermont, went on to the French Culinary Institute in New York, and worked as a chef for several years. Skip was supportive of Nick’s career, telling him he would be the first investor in any restaurant his son opened.

By 2008, things had changed. Nick had gotten married (wearing a pair of black Bally wingtips made from Horween leather that had belonged to Skip), and the sagging economy was taking a toll on the private chef business where he worked. His wife was also looking for a new job. Their lease was up. The time seemed right to move back to Chicago and rejoin Horween, learning what Nick described as “the more complicated, upper levels of the business.“ He sees similarities between cooking and making leather, even if the tannery can sometimes operate in ways that ruffle a classically trained chef’s sense of order and efficiency. Once he gently suggested to an employee that he rearrange his work station, only to get a long look from a man who, Nick realized, had been at Horween longer than Nick had been alive.

“I walk around and cringe a little bit sometimes, but it’s part of the personality of the place,” Nick said. “There’s a lot of autonomy here and you have to let people set themselves the way that works best for them, because that’s the way the product is. It’s not all about efficiency. It’s about the product … You take something that’s a raw material, that’s not uniform, and you’re trying to make it the same in the end every time.”

The processes for making Horween’s signature leathers like shell cordovan and Chromexcel, a rich and versatile cowhide, can’t be rushed. Shell cordovan comes from the inner membrane of the horse posterior. The horse butts are draped over rods and submerged in “pits,” or low pools filled with Horween’s proprietary vegetable tanning solution made from tree barks, for 30 days. After tanning, the hides are carefully shaved, a process that exposes the outline of the inner membrane, and steeped in a second pit of stronger solution for another 30 days. When they come out, they’re hand-oiled. Then, after a three-month rest, they have to be re-wet and shaved again on a machine whose blade is controlled with a foot pedal.

Only three workers at Horween can do this job, which Nick described as one of the most skilled positions at the tannery. Trimming too little results in a rough-feeling hide; trimming too much cuts into the membrane and results in downgraded leather. The cordovan then goes through a machine with a large roller that applies several light coats of non-pigmented dye and is left to dry. The finished product is shiny, smooth, and durable.

Today, the company’s primary constraint on shell cordovan production is one of supply. It gets hides from French-speaking Canada and parts of Europe where people still eat horsemeat, a practice that is dwindling. Because there aren’t enough shells to keep up with customer demand, the tannery has to turn down new requests for its cordovan.

Only 10 percent of the hides Horween processes come from horses. The other 90 percent is cowhide, primarily steer, that the tannery buys from large meat producers like Tyson. The cow hides for Chromexcel are tanned with a chrome-based solution in large drums. When the hides emerge from their bath, they are a pale baby blue color and the story of the animal is still clearly written on the skin: bug bites, barbed wire scratches, brands. The hides are re-tanned with vegetable-based solutions and then “hot stuffed,” or conditioned with unrefined oils and greases, per customer specifications for texture and color. The hot stuffing process creates a coveted effect called “pull-up,” where creasing or folding the leather causes a temporary lightening in color as the oils and waxes are displaced.

We’re not cheap. If you came to me and said, ‘Wow, I need a million of something in a really big hurry,’ you’re probably in the wrong place.

“It needs to be the best it can be because that’s really our competitive advantage,” Skip said. “We’re not cheap. If you came to me and said, ‘Wow, I need a million of something in a really big hurry,’ you’re probably in the wrong place.”

Rose Bowl to Super Bowl

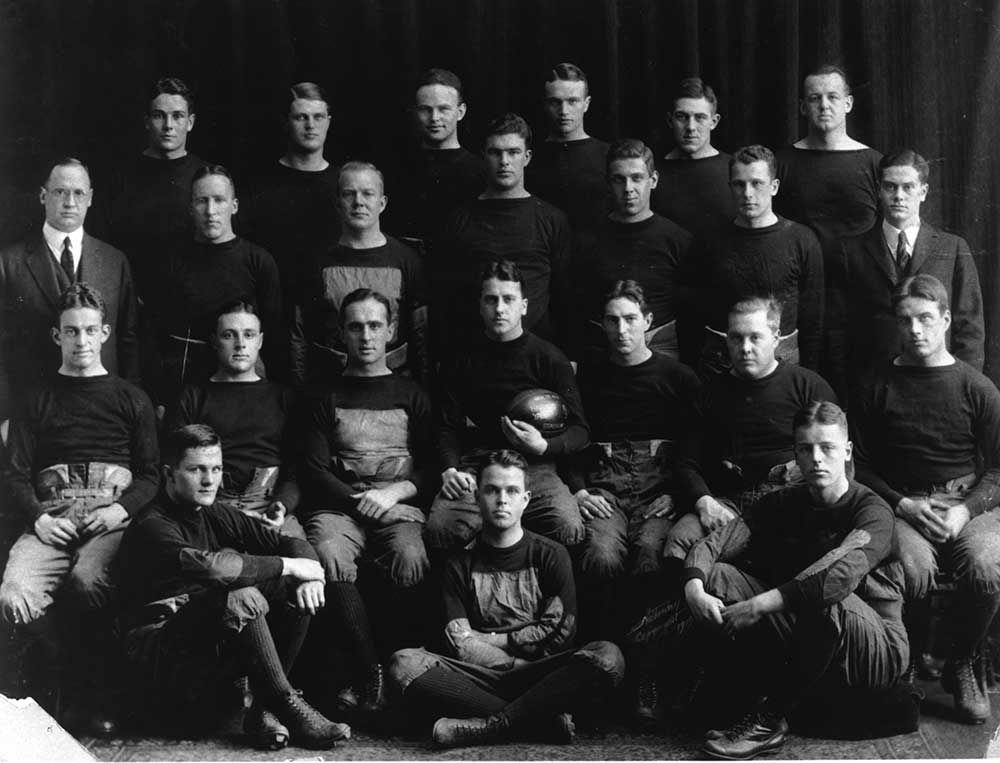

Horween’s consistency helped win and keep the business of Wilson Sporting Goods Co., the NFL’s official ball maker. Football is a major part of both Horween family history and the story of the business. Arnold Horween Sr. and his brother, Ralph, played on the Harvard team that won the 1920 Rose Bowl. Then they went pro, playing for the Chicago Cardinals—but using the fake surname “McMahon” to hide their activity from their mother, fearing her disapproval. Arnold Horween Sr. later coached the team at his alma mater and Arnold Horween Jr. was also a Harvard football player. (Skip grew up playing ice hockey.)

The elder Horweens’ football careers put them in contact with George Halas, the founder and owner of the Chicago Bears. That connection in turn helped make Horween a near-exclusive provider of leather for Chicago-based Wilson. The tannery makes football leather from cowhide (not pigskin) for Wilson, as well as big manufacturers like Nike, Adidas and Spalding. A 1,000-ton press outfitted with German-made embossing plates gives the leather its distinctive pebbling, while a proprietary finishing process called “tanned in tack” imbues the leather with a stickiness that allows players to more easily grip the ball.

“We really try and make those guys know we don’t take (the Wilson relationship) for granted,” Skip said. “That’s a piece of business that lots of people would like to do.”

The hallway outside Skip and Nick’s offices is lined with framed pieces of Super Bowl game balls. The tannery is full of memorabilia, which Nick often photographs for the company blog. He’s discovered decades-old customer lists with names like Chrysler, Studebaker and John Deere, which once used Horween leather for seals and gaskets. Producing this “mechanical leather,” along with Chromexcel for shoes worn by the Marine Corps, kept the tannery busy during World War II.

And while the company has made modern upgrades to keep pace with environmental regulations, such as operating its own water treatment plant, much of the equipment on Horween’s factory floor is vintage. Nick has a photo of his great grandfather, Arnold Horween Sr., operating one of the foot pedal-controlled machines for shaving cordovan that are still in use today.

In Nick’s office, he sits at a desk that belonged to his great grandfather. He also modeled his business cards after the ones Arnold Horween Sr. carried, even asking the letterpress stationer to track down the same serif used on the original. Nick’s office is stuffed with Horween mementos that, despite their age, look like they could stand more years of use: A weathered pair of brown work boots that his grandfather wore during summers at the family’s Michigan vacation home, a collection of leather razor strops stamped with the tannery’s name.

Nick sees his grandfather as belonging to a generation of “guys that had three or four really nice suits and that’s all they had. And then there was the next generation that wanted the deals. They wanted 50 suits that were buy-one-get-one-free and all that stuff. And I think people have gone back the other way, which is great for us because that’s where we live.”