Listen to the audio version of this story. For more, subscribe to our podcast.

Almost every day of the week, Erik Bauer wears a Hollymatic Corporation polo shirt sporting the company’s logo. It’s a row of six identical red dots above a black line, representing freshly molded hamburger patties on a conveyor belt.

“But not everybody gets that,” says Bauer, Hollymatic’s corporate director of sales and marketing. “They say, ‘Hey, look at the red balls!’”

Not everybody knows about Hollymatic’s role in the history of American fast food, either. The company was founded in 1937 by Harry Holly, a laid-off ironworker who opened a tiny hamburger stand in the Chicago area during the Depression and then invented a machine to make more uniform patties in a shorter period of time. In the early days of the fast food industry, Holly’s patty press could be found at McDonald’s, Burger King and Wendy’s restaurants.

“I don’t think they ever gave credit to the guy,” says Jim Azzar, the owner of Hollymatic since 1988 and Bauer’s father-in-law. “He was the inventor of the mass-produced fast food hamburger.”

That Holly’s contributions went unappreciated is a result of both far-reaching changes in the fast food industry and turmoil at Hollymatic, which suffered financial losses and management upheaval that ousted the founder from his own company. Azzar, who runs a vertically integrated group of businesses related to meat processing, has fashioned Hollymatic into a niche player that caters to small and mid-sized restaurants, butcher shops and grocery stores. Where the company once supplied McDonald’s and Burger King with patty machines, its equipment now helps make alternatives to Big Macs and Whoppers.

People are asking for local. People are asking for fresh and that’s starting to make a real swing back.

“We call them hockey pucks,” Azzar says of fast food patties. “It’s a frozen hamburger that’s made en masse. … By the time it comes to you in a store, it could have been frozen for 90 days and there’s no juiciness to it.”

A renewed interest in fresh food among gastronomically minded consumers has reopened markets that Hollymatic ceded years ago. One example is grocery stores, whose meat counters have been shifting from selling “case-ready” products — meat that is processed and packaged elsewhere — to grinding meat to order. Hollymatic recently exhibited at a major grocery store trade show for the first time in 10 years, seeking to reintroduce the company to that industry.

“People are asking for local,” Bauer says. “People are asking for fresh and that’s starting to make a real swing back.”

Harry’s hamburger machine

Harry Holly and his wife, Agnes, opened Harry’s Hamburgers under his grandmother’s porch stairs in Calumet City, Ill., in the early 1930s. Hamburgers cost a nickel apiece, as did slices of Agnes’ homemade pie. On the first day, Harry’s Hamburgers sold 80 cents worth of food. The restaurant relocated several times as business grew, eventually landing in Chicago. Frustrated with forming hamburgers by hand, a time-consuming process that resulted in inconsistent patty weights, Holly invented a wooden molding machine. One of the original presses, which inspired the steel version Holly patented in 1937, is on display at Hollymatic’s headquarters in Countryside, Ill., about 15 miles southwest of Chicago.

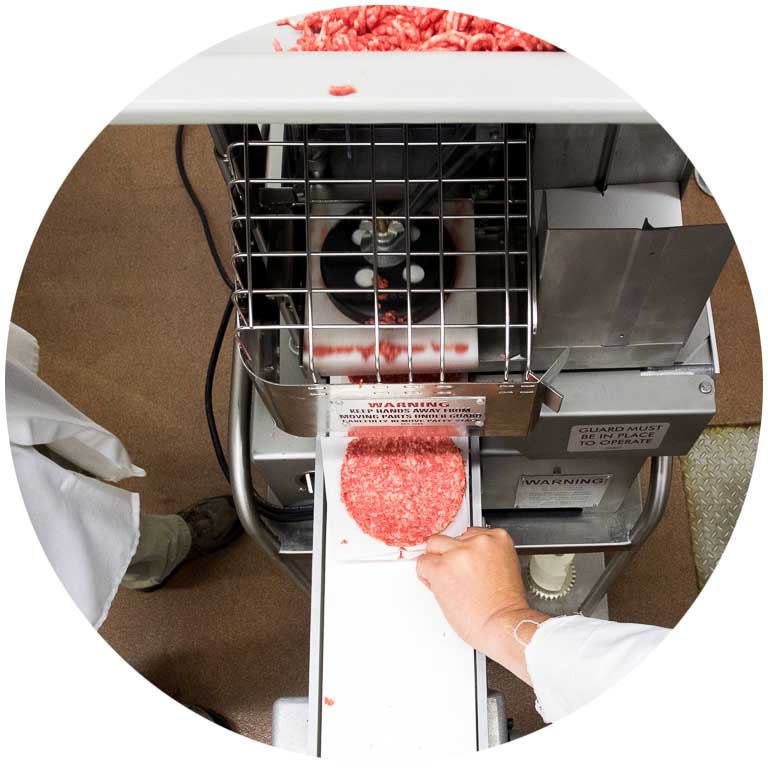

The company’s current bestseller, the Super patty machine, looks quite different from Holly’s wooden press but at its heart remains close to the inventor’s vision of efficiency and reliability. Originally named the Super 54 for the year it was developed, the machine fits on a countertop and can produce 2,100 patties an hour. Ground meat is fed through a large hopper on top and gets squeezed through a narrow compartment before being molded into patties, each one knocked out of the machine with a distinctive “thunk” sound. The Super stacks the finished patties, automatically sliding a square of waxed paper between each one, and moves the columns down the conveyor belt.

Hollymatic developed a network of equipment dealers across the country. Azzar’s father ran one of those businesses; his company, Azzar Store Equipment, was based in Grand Rapids, Mich., and sold patty machines in the western half of the state. Azzar, who would go on to own Hollymatic, was born in 1947 and started going on service calls for the family business when he got his driver’s license at 16. He still works out of Azzar Store Equipment’s office in Grand Rapids.

Azzar’s childhood overlapped with the beginnings of the fast food industry. Ray Kroc opened his first McDonald’s in Des Plaines, Ill., in 1955, and Hollymatic outfitted the burger chain with patty machines. The relationship was so fruitful that in 1961, the two companies said they were jointly developing a machine whose hourly patty output would double that of the previous model.

But McDonald’s rapid growth soon left Hollymatic behind. By the late 1960s, the fast food chain had “moved to a different system that allowed the company to best serve its growing customers,” according to a McDonald’s spokeswoman. Today, the corporation’s restaurants receive shipments of frozen patties made in large quantities at a central facility.

Hollymatic’s other fast food customers made similar transitions to a central processing system. By the 1980s, the company had lost its last major fast food chain, Wendy’s. In the meantime, Hollymatic introduced new products, such as a mixer grinder machine. Holly also encouraged a friend to start a specialty paper business to supply Hollymatic with patty paper, the small waxy squares separating freshly pressed burgers. The resulting company, Bomarko, merged into Hollymatic in 1968.

Hollymatic Corp. went public in 1971. A year later, it opened a 25,000-square-foot research and development facility in Boca Raton, Fla., where Holly had a large house with a ballroom and helipad. By the late 1970s, however, profits were falling. Holly also missed a major opportunity when a Hollymatic engineer, Lou Richards, pitched him on a hydraulic patty machine. As Bauer tells it, “Harry basically said, ‘If there’s going to be an innovation in hamburger patty forming, it’ll come from me.’” Richards left Hollymatic to start a company called Formax, which manufactures large-scale meat processing equipment. Hollymatic stuck to smaller machines like the Super, which remains the industry’s standard for patty equipment of that size.

Formax’s market is “certainly a spot that Hollymatic would have wanted, but at this point, that ship has sailed,” Bauer says.

Azzar is more blunt about the rejection of Richards’ idea: “There was no depth at Hollymatic at the time. They weren’t survivalists.”

In 1978, the company’s board of directors voted to replace Holly with Philip Clarke Jr., the investment banker who had led Hollymatic’s initial public offering. (Complicating matters, Clarke was Holly’s son-in-law. The two men reconciled years later, Clarke’s son told the Chicago Tribune when Clarke died in 2007.) The Boca Raton R&D center and a Swiss subsidiary were put up for sale. That first board revolt kicked off a series of internal power struggles, recriminations and turnover in the upper ranks. As the drama spilled into the early 1980s, the meat equipment business languished and Hollymatic came to rely on the Bomarko specialty paper division for profits.

“Everyone thought Hollymatic was down for the count,” says Azzar, who by then was working in the plastics industry. “I’m a contrarian, I guess, so I started buying stock in Hollymatic.”

Azzar estimates he owned about 30 percent of the company by the early 1980s. In 1982, Hollymatic announced plans to sell its equipment division to a group consisting of a company officer and three independent dealers, leaving Bomarko as a standalone company. Azzar tried making his own bid for control, but the sale went through over his objections. Six years later, Azzar bought Hollymatic from the group of dealers. He also acquired Bomarko and re-purchased Hollymatic’s Swiss subsidiary.

After those transactions, Azzar says, “other than the research center they had in Boca Raton, what was torn apart was put back together.”

A burger business reborn

Hollymatic and Bomarko are part of a business portfolio Azzar has built over the last few decades, partially inspired by Henry Ford’s strategy of vertical integration. In 2005, Azzar bought Peshtigo, Wisc.-based Badger Paper Mills to be a supplier to Bomarko, which makes wrappers for Wrigley gum and Johnson & Johnson Band-Aids bandages in addition to patty paper. Azzar’s other companies include Rollstock, a manufacturer of vacuum packaging equipment (think of the plastic tube encasing a Slim Jim beef jerky stick) and NuTEC, a maker of large-scale meat processing machines capable of producing a million chicken nuggets per hour.

Azzar has been repeatedly entangled in litigation related to his business deals, including the Bomarko and Badger Paper Mills transactions. Allen Kahn, an executive who fought Azzar in court over Bomarko, is quoted in a 1988 Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel story as saying: “I have got to be damn careful here. This guy is someone one has to be extremely prudent with.”

On the phone and in person, Azzar is good-natured with a dry sense of humor. And he expresses a particular fondness for Hollymatic. When Holly died in 1997, he took out a full-page ad in the Wall Street Journal to honor the inventor.

“I ate the first 30 years of my life because of Hollymatic and the dealership we had,” Azzar says.

Equipment dealers and customers have stuck with Hollymatic over generations. The U.S. Department of Defense, for example, has contracted with Hollymatic since the 1980s to outfit military commissaries with mixer grinders. The oldest known working Hollymatic patty machine, a Super from 1959, resides at Triple XXX Family Restaurant in West Lafayette, Ind. The 85-year-old restaurant uses 100 percent top sirloin and grinds it in-house to make its burgers, which are cooked to order. During busy times, the Hollymatic Super runs continuously for 60 to 90 minutes and stamps out a patty every two seconds. Restaurant co-owner Greg Ehresman replaces the machine’s bolts occasionally but has never seen it break down.

A good design is a good design, period.

“A good design is a good design, period,” says Ehresman, who eats at least one of his restaurant’s burgers a day. “The wheel is round for a reason. Making it square’s not gonna help you.”

These days, Hollymatic is courting more restaurant chains and grocery stores. This reverses a decade-old decision to shift from supermarkets to small meat processors. Consolidation and closings in the latter industry have thinned the customer base.

“Where in Grand Rapids, we might have had 25 small processors in a 100-mile radius around us, we’re probably down to four or five,” Bauer says. “So it really changed the landscape quite a bit and it’s hard to make a living selling one or two machines at a time.”

Hollymatic is also looking to fine-tune the patty machine’s basic premise: make homemade-tasting burgers faster while keeping size and weight consistent. While the company has left the look of the machines largely unchanged over the last 50 years, it has added safety features and a system called Roto-Flow that squeezes ground meat through holes on a rotating plate.

“As it spins, these twines of meat are being knitted together and there’s also air pockets that are in between,” says Rob Kovacik, a 34-year employee who is Hollymatic’s corporate manager of sales and marketing, as well its unofficial historian. “It actually cooks faster. … It lays flatter on the grill and it’s just a more tender patty. It really makes a difference.”

The company’s current R&D efforts are focused on digital features, such as replacing a patty machine’s dials and push buttons with touchscreen controls for variables like timing and compression. Bauer believes customers like supermarket chains benefit from collecting data across machines in multiple locations.

“Now I can take a look and say…this guy is mixing it longer than that guy. We’ve got to get them back into line so all the meat tastes the same from every store. On top of that, how much energy is (the machine) using, how long did it run, do we need to replace that machine,” he says. “You can start to use those things for maintenance. There’s just a lot of opportunity here for improvement.”

The only Holly family member still working in the meat equipment industry is Bobby “the Burger” Chura. Holly was his great-grandfather on his mother’s side. Chura’s paternal grandfather was a Chicago butcher who became a Hollymatic dealer in the 1950s. Chura works at a food equipment distributor called Berkel Midwest, servicing machines at butcher shops and grocery stores in the region. Many of his customers’ parents and grandparents knew his father and grandfather.

Even today, there’s no machine on the market that can compete with that machine.

Although he’s friendly with Bauer, Chura says he’s never considered working at Hollymatic. Still, he loves extolling the virtues of Hollymatic patty makers — their design, their speed, and their ability to produce consistent burgers down to the gram. Chura still sees the Super in the majority of the restaurants he visits.

“Just the way that machine operates is genius,” Chura says. “Even today, there’s no machine on the market that can compete with that machine.”